English

The number of children reporting they experience child abuse is alarmingly high on Aruba. A pattern that is hard to break, says researcher Clementia Eugene. But there is hope: when parents receive the right resources and support, things can change. “When people know better, they do better.”

Next article

Share this page

Table of contents

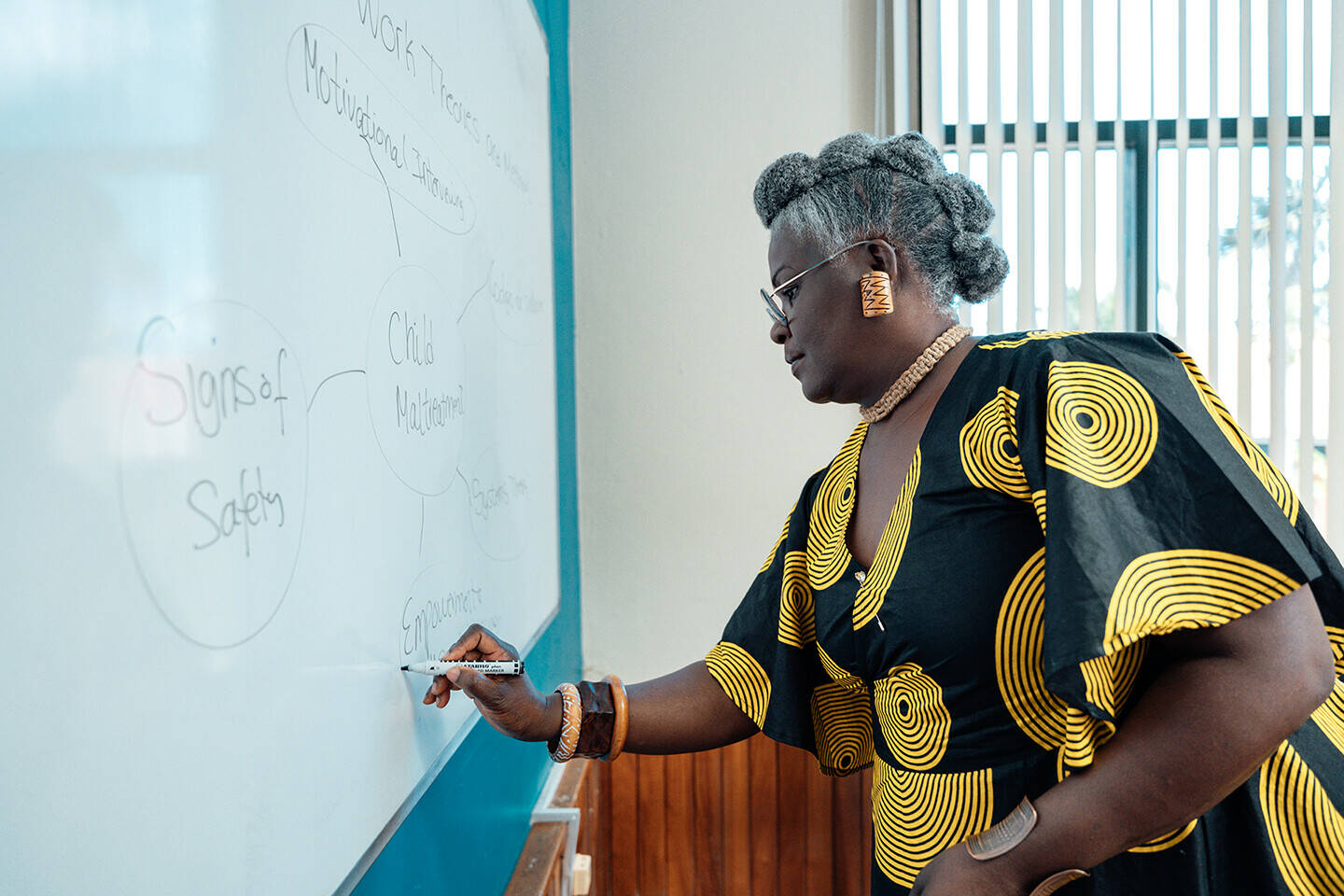

Clementia Eugene, MSW, a graduate of Howard University among others, is a PhD candidate and Lecturer at the Department of Social Work and Development, Faculty of Arts and Science at the University of Aruba. She was also the Director of Human Services and Family Affairs in Sint Lucia before coming to Aruba. Her motivation to conduct this study on child maltreatment derived from her passion in child protection work as a social work practitioner and academic educator. “Additionally, my motivation is influenced by my innate belief that children’s lives matter, and if we want to predict what the life of adults and the society will look like in the future, we must look at how children are treated in the present moment.”

About

Clementia Eugene

“The Codigo is spot on in terms of providing professionals with clear, easy steps that they can use when they suspect a case of child abuse”

The Codigo di Proteccion, CdP, is also an excellent tool to work on prevention. It encompasses strategies to end violence against children, including implementation and enforcement of laws relating to policies and reporting of child abuse. “The Codigo is spot on in terms of providing professionals within the health, education, justice and social services sectors, with clear, easy steps that they can use when they suspect a case of child abuse. It is harmonised and I think it is excellent. The preliminary results of the impact of CdP are very promising,” Eugene concludes.

Perhaps, with the right steps, children in Aruba may have a more joyful story to tell after all.

It is imperative for all student teachers to take compulsory courses on how to teach children how to handle their emotions, rather than just academics. The topic has to be front and centre in order to prevent abuse. “That is when we put human beings and children at the centre of human development. We do need economic development, but children have to be at the centre of development.” Eugene is convinced these steps are doable and cost effective. “We can use technology to provide, for instance, twenty episodes of an online course, lasting ten minutes each, for teachers and parents in their workplaces, through the Human Resource Departments as part of a mass educational campaign. The system registers when staff logs in to listen to the online child abuse educational series and completes the evaluation quiz.”

The right steps

Interview

7 min

PhD candidate and Lecturer at the University of Aruba

Clementia Eugene

“Let’s educate ourselves”

Let’s make sure everyone in the room makes a commitment that ‘I will never perpetuate this type of violence in the family that I will create, as a teacher in my classroom, as a supervisor at my work or in any other setting’

The results show that 78.4% of the children in the study have experienced some kind of abuse in their lifetime. When the data was aggregated based on what the children experienced in the last 12 months of the study, the result was 50%. Physical abuse was reported the most, followed by emotional abuse. The least prevalent was neglect, contrary to numbers from other entities in Aruba.

Results

Scroll down

From the study it is clear that age, gender and socio-economic status are predominant predictive factors of abuse. This means that the older the children, the higher the risk of being subjected to sexual abuse, physical and emotional abuse, and witnessing interparental violence. Gender is also a predictor for witnessing interparental violence,” Eugene explains. “More girls than boys reported having witnessed interparental violence. Socio-economic status is also a predictive factor whereby the lower the socioeconomic status of the family, the more likely it is that the children experience neglect and witness interparental violence.” The higher the academic level of the fathers, the less likely children are to experience domestic violence, particularly interparental violence in the homes. This is also in line with global trends.

Eugene informed that the study revealed that children tell their teachers, mentors and friends in schools when they are abused. Preventing further abuse requires educating this group on early indicators of all sorts of abuse, Eugene explains, “So when children talk, they can give it a name, they can label it and give their peers advice on where to go for help. We need to empower schools, youth clubs, sport clubs, everywhere children go.”

While the education and health system in Aruba are the biggest assets to curtail violence against children, Eugene still believes there is room for improvement here. She compared the Aruba data with the few studies done in the region, concluding as probable cause that in the Caribbean we have not been socialised to communicate our emotions, our thoughts, and ask for what we want. “Effective communication is not something Caribbean people have mastered. We were taught to be inferior to our colonials, and we have passed these negative values to our children.”

Studies recommend social and emotional learning in schools and also for parents to better manage and control their own emotions, to be able to better communicate their thoughts without needing to resort to shouting and also how to say no. “As Caribbean people, we are not very assertive in our language and that is passed on from generation to generation,” Eugene continues. “That is what I have discovered in the relevant literature and it can be applied to Aruba as well.” Aruba has the additional complication of having a Dutch language-based education, while most people speak Papiamento. “How can children express their emotions in school, in a language that is not their own? The education system therefore limits children learning to communicate and to express thoughts, emotions, and beliefs and what they want, and in turn minimise emotional abuse.”

The system has to be consistent, though. In Sint Lucia, her native country, Eugene facilitated many parental guidance programs, that were deemed successful in term of active participation. Yet within months the parents went back to the old ways of disciplining children using harsh punishment. “Why? Because this cycle of violence is endemic in our community. We are moving from one generation to the next without healing the wounds of the past.” Eugene recommends an intergenerational approach to the prevention of child maltreatment. This requires gathering families of multiple generations in one room to tell their stories of abuse and educate themselves about the impact of abuse. The next step is for everyone in the room to make the commitment that ‘I will never perpetuate this type of violence in the family that I will create and in my professional life. For example, as a teacher in my classroom, as a supervisor at my work or in any other setting, I will not perpetuate violence of any kind.’”

Educating parents is key, as they are primarily responsible for the socialisation of children, Eugene states. “If these parents come from a home where they have experienced violence, violence becomes intergenerational. But: when people know better, they do better. When they have resources, they do better and when supported by a strong monitoring and evaluating system, parents can do better.”

In order to better measure the wellbeing in Aruba, particularly that of children, it is time to switch our mindset and let go of Gross Domestic Product, GDP, as the most important indicator of quality of life. Instead of this Eugene argues the merit of the theoretical framework of the Human Capabilities Approach, (HCA), which entails ten capabilities, that include life, bodily health, integrity, emotions and control over one’s environment. Measuring development based on GDP, necessary for a country’s income, places the economy at the centre. “My argument is that this does not say much about the quality of life of people or specifically that of children.”

To make the switch to HCA, Aruba needs to develop a capability-based, child friendliness index, using the ten capabilities as the gold standard to measure how well our children are doing. The child friendliness index would be the principal instrument to measure the quality of life of our children in all domains of life in terms of health, education and spiritual, emotional and psychological wellbeing, using the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child as the baseline, Eugene says. One way of determining how well a country is doing is to ask how our children are doing, because they will grow to become adults who will bring their psychosocial challenges and baggage with them, which will impact their quality of life and their ability to be productive. Additional benefit: it is also a positive way to call attention to the issue, instead of focusing on the negative. “The government, in charge of policies has to spearhead the transition to HCA. However, it is also the responsibility of social workers, educators, health professionals and the social justice system to apply this approach. It creates an environment for children to flourish, as the prevention of child abuse is at its core.”

Alarming figures, according to Eugene. “This means, on average, that eight of every ten children experience abuse.” There is a reason why the figure for neglect differs greatly in other studies, she explains. “The numbers I present are based on the children’s own lived experiences. Other studies, based on teachers’ observations who notice when children attend school poorly dressed or hungry, present different results. It is evident when neglect becomes more prevalent. But teachers may not easily observe emotional or even physical abuse.” Moreover, children may have a different interpretation of neglect.

Boys and girls experience abuse equally. However, more boys are experiencing sexual abuse outside the family, while girls within. This phenomenon is in line with that of other Caribbean nations and globally.

Sadly, when children in Aruba tell their story, for many, it is no fairy tale. That is the conclusion of the study ‘Prevalence of Child Maltreatment and Human Capabilities in Aruba,’ by Clementia Eugene, lecturer and PhD candidate at the University of Aruba. The objective of the study was to provide national prevalence estimates of child maltreatment, theorise child maltreatment in a much broader context of child development and to enhance policies and targeted prevention programs and intervention services to protect children in Aruba. “It is important to recognise that the results of the study are coming from a school-based survey,” Eugene explains. “These are the self-reported experiences of children.”

Violence is preventable

Wellbeing

Predominant factors

Assertive communication

We need to empower schools, youth clubs, sport clubs, everywhere children go.

Share this page

English

Next article

Table of contents

“The Codigo is spot on in terms of providing professionals with clear, easy steps that they can use when they suspect a case of child abuse”

The Codigo di Proteccion, CdP, is also an excellent tool to work on prevention. It encompasses strategies to end violence against children, including implementation and enforcement of laws relating to policies and reporting of child abuse. “The Codigo is spot on in terms of providing professionals within the health, education, justice and social services sectors, with clear, easy steps that they can use when they suspect a case of child abuse. It is harmonised and I think it is excellent. The preliminary results of the impact of CdP are very promising,” Eugene concludes.

Perhaps, with the right steps, children in Aruba may have a more joyful story to tell after all.

It is imperative for all student teachers to take compulsory courses on how to teach children how to handle their emotions, rather than just academics. The topic has to be front and centre in order to prevent abuse. “That is when we put human beings and children at the centre of human development. We do need economic development, but children have to be at the centre of development.” Eugene is convinced these steps are doable and cost effective. “We can use technology to provide, for instance, twenty episodes of an online course, lasting ten minutes each, for teachers and parents in their workplaces, through the Human Resource Departments as part of a mass educational campaign. The system registers when staff logs in to listen to the online child abuse educational series and completes the evaluation quiz.”

The right steps

Eugene informed that the study revealed that children tell their teachers, mentors and friends in schools when they are abused. Preventing further abuse requires educating this group on early indicators of all sorts of abuse, Eugene explains, “So when children talk, they can give it a name, they can label it and give their peers advice on where to go for help. We need to empower schools, youth clubs, sport clubs, everywhere children go.”

We need to empower schools, youth clubs, sport clubs, everywhere children go.

While the education and health system in Aruba are the biggest assets to curtail violence against children, Eugene still believes there is room for improvement here. She compared the Aruba data with the few studies done in the region, concluding as probable cause that in the Caribbean we have not been socialised to communicate our emotions, our thoughts, and ask for what we want. “Effective communication is not something Caribbean people have mastered. We were taught to be inferior to our colonials, and we have passed these negative values to our children.”

Studies recommend social and emotional learning in schools and also for parents to better manage and control their own emotions, to be able to better communicate their thoughts without needing to resort to shouting and also how to say no. “As Caribbean people, we are not very assertive in our language and that is passed on from generation to generation,” Eugene continues. “That is what I have discovered in the relevant literature and it can be applied to Aruba as well.” Aruba has the additional complication of having a Dutch language-based education, while most people speak Papiamento. “How can children express their emotions in school, in a language that is not their own? The education system therefore limits children learning to communicate and to express thoughts, emotions, and beliefs and what they want, and in turn minimise emotional abuse.”

Assertive communication

Let’s make sure everyone in the room makes a commitment that ‘I will never perpetuate this type of violence in the family that I will create, as a teacher in my classroom, as a supervisor at my work or in any other setting’

The system has to be consistent, though. In Sint Lucia, her native country, Eugene facilitated many parental guidance programs, that were deemed successful in term of active participation. Yet within months the parents went back to the old ways of disciplining children using harsh punishment. “Why? Because this cycle of violence is endemic in our community. We are moving from one generation to the next without healing the wounds of the past.” Eugene recommends an intergenerational approach to the prevention of child maltreatment. This requires gathering families of multiple generations in one room to tell their stories of abuse and educate themselves about the impact of abuse. The next step is for everyone in the room to make the commitment that ‘I will never perpetuate this type of violence in the family that I will create and in my professional life. For example, as a teacher in my classroom, as a supervisor at my work or in any other setting, I will not perpetuate violence of any kind.’”

Educating parents is key, as they are primarily responsible for the socialisation of children, Eugene states. “If these parents come from a home where they have experienced violence, violence becomes intergenerational. But: when people know better, they do better. When they have resources, they do better and when supported by a strong monitoring and evaluating system, parents can do better.”

Violence is preventable

In order to better measure the wellbeing in Aruba, particularly that of children, it is time to switch our mindset and let go of Gross Domestic Product, GDP, as the most important indicator of quality of life. Instead of this Eugene argues the merit of the theoretical framework of the Human Capabilities Approach, (HCA), which entails ten capabilities, that include life, bodily health, integrity, emotions and control over one’s environment. Measuring development based on GDP, necessary for a country’s income, places the economy at the centre. “My argument is that this does not say much about the quality of life of people or specifically that of children.”

To make the switch to HCA, Aruba needs to develop a capability-based, child friendliness index, using the ten capabilities as the gold standard to measure how well our children are doing. The child friendliness index would be the principal instrument to measure the quality of life of our children in all domains of life in terms of health, education and spiritual, emotional and psychological wellbeing, using the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child as the baseline, Eugene says. One way of determining how well a country is doing is to ask how our children are doing, because they will grow to become adults who will bring their psychosocial challenges and baggage with them, which will impact their quality of life and their ability to be productive. Additional benefit: it is also a positive way to call attention to the issue, instead of focusing on the negative. “The government, in charge of policies has to spearhead the transition to HCA. However, it is also the responsibility of social workers, educators, health professionals and the social justice system to apply this approach. It creates an environment for children to flourish, as the prevention of child abuse is at its core.”

From the study it is clear that age, gender and socio-economic status are predominant predictive factors of abuse. This means that the older the children, the higher the risk of being subjected to sexual abuse, physical and emotional abuse, and witnessing interparental violence. Gender is also a predictor for witnessing interparental violence,” Eugene explains. “More girls than boys reported having witnessed interparental violence. Socio-economic status is also a predictive factor whereby the lower the socioeconomic status of the family, the more likely it is that the children experience neglect and witness interparental violence.” The higher the academic level of the fathers, the less likely children are to experience domestic violence, particularly interparental violence in the homes. This is also in line with global trends.

Alarming figures, according to Eugene. “This means, on average, that eight of every ten children experience abuse.” There is a reason why the figure for neglect differs greatly in other studies, she explains. “The numbers I present are based on the children’s own lived experiences. Other studies, based on teachers’ observations who notice when children attend school poorly dressed or hungry, present different results. It is evident when neglect becomes more prevalent. But teachers may not easily observe emotional or even physical abuse.” Moreover, children may have a different interpretation of neglect.

Boys and girls experience abuse equally. However, more boys are experiencing sexual abuse outside the family, while girls within. This phenomenon is in line with that of other Caribbean nations and globally.

Sadly, when children in Aruba tell their story, for many, it is no fairy tale. That is the conclusion of the study ‘Prevalence of Child Maltreatment and Human Capabilities in Aruba,’ by Clementia Eugene, lecturer and PhD candidate at the University of Aruba. The objective of the study was to provide national prevalence estimates of child maltreatment, theorise child maltreatment in a much broader context of child development and to enhance policies and targeted prevention programs and intervention services to protect children in Aruba. “It is important to recognise that the results of the study are coming from a school-based survey,” Eugene explains. “These are the self-reported experiences of children.”

Wellbeing

Predominant factors

The number of children reporting they experience child abuse is alarmingly high on Aruba. A pattern that is hard to break, says researcher Clementia Eugene. But there is hope: when parents receive the right resources and support, things can change. “When people know better, they do better.”

Interview

7 min

PhD candidate and Lecturer at the University of Aruba

Clementia Eugene

“Let’s educate ourselves”

The results show that 78.4% of the children in the study have experienced some kind of abuse in their lifetime. When the data was aggregated based on what the children experienced in the last 12 months of the study, the result was 50%. Physical abuse was reported the most, followed by emotional abuse. The least prevalent was neglect, contrary to numbers from other entities in Aruba.

Results

Clementia Eugene, MSW, a graduate of Howard University among others, is a PhD candidate and Lecturer at the Department of Social Work and Development, Faculty of Arts and Science at the University of Aruba. She was also the Director of Human Services and Family Affairs in Sint Lucia before coming to Aruba. Her motivation to conduct this study on child maltreatment derived from her passion in child protection work as a social work practitioner and academic educator. “Additionally, my motivation is influenced by my innate belief that children’s lives matter, and if we want to predict what the life of adults and the society will look like in the future, we must look at how children are treated in the present moment.”

About

Clementia Eugene